Leanda de Lisle, author of ‘The Sisters Who Would Be Queen: The Tragedy of Mary, Katherine and Lady Jane Grey’ has written a guest article for the blog.

Thanks to Leanda de Lisle, Harper Collins and the National Gallery.

DEATH BECOMES HER – BY LEANDA DE LISLE

The legend of Jane Grey, the teenage Queen sacrificed to a mother’s ambition, is encapsulated in Paul Delaroche’s historical portrait of her execution. It is an image with all the erotic overtones of a virgin sacrifice. But behind the myths lies a true story of fraud, misogyny, sadomasochism and an innocent mother defamed.

The Execution of Lady Jane Grey, 1833

Oil on canvas

(c) The National Gallery, London

So who was Jane Grey, the future Nine Days Queen? A great niece of Henry VIII, Jane was, under the terms of his will, the heir to his children Edward, Mary, and Elizabeth Tudor. At the time of his death it seemed unlikely Jane would ever become Queen in her own right. But Jane’s father, Harry Grey, hoped she would one day marry the new King, Edward VI. He gave her an education suitable for a Protestant Queen consort. But it is Jane’s royal mother, Frances, whom historians have credited with the lion’s share of family ambition.

The historian Alison Weir follows others in describing Frances as a woman “greedy for power and riches,” who “ruled her husband and daughters tyrannically and, in the case of the latter, often cruelly” They quote as evidence for the accusation of abuse a story written over a decade after Jane was beheaded. Elizabeth Tudor’s former tutor, Roger Ascham, recalled finding the thirteen-year old Jane reading Plato in Greek in the hall at her parents’ house, while the rest of the household were hunting in the park. Jane explained she preferred her books to the park because lessons with her kindly tutor provided a respite from her parents who would pinch or smack her if she didn’t stand, sit, and do everything perfectly.

Ascham was, however, writing to an agenda: his wish to change the harsh discipline commonplace in the schoolroom. At the time he met Jane he had commented only on her parents’ pride in her work. Jane’s ‘kindly’ tutor was, meanwhile, asking for advice on how to ‘bridle’ the complaining teenager. He described her as at ‘that age’ when ‘all people are inclined to follow their own ways’. Teenagers had a reputation for stroppiness even in the sixteenth century.

Historians should take Ascham’s story with a pinch of salt. Instead they pile invented details on it. Their claim that Frances was a fanatical huntress inspired a scene in Trevor Nunn’s 1985 film, Lady Jane Grey. In it Frances is seen preparing to slaughter a deer on snow: an image that establishes her early on in the film as a destroyer of innocents. A history for children, published this month, adds that Frances would force Jane to go hunting, a sport Jane ‘hated’: something most unlikely in this period.

But if Frances was not a notably cruel mother, what of the accusation that she sacrificed her daughter’s life to greed and ambition?

By May of 1553, when Jane turned sixteen, it was evident that Edward VI was dying. To prevent his Catholic half sister, Mary Tudor from inheriting the throne Edward excluded his sisters from the succession. He did so on grounds of their illegitimacy: Henry VIII did not believe in divorce and had his marriages to their mothers annulled. In their place Edward wanted to name a male heir. And in order that Jane might have a son, she was married to Guildford Dudley, son of the head of Edward’s Privy Council, John Dudley.

Historians describe Jane’s parents beating her into agreeing to this marriage. But there is no contemporaneous evidence for this. Certainly Frances would later insist she had opposed it, and it was also said that Jane had. But this was connected a campaign to scapegoat the Dudleys for what happened next.

When it became evident there was no time for Jane to have a son before Edward died, the King altered his will. On July 6th he bequeathed Jane the throne directly. There is a famous eye witness account of Jane being processed to the Tower as Queen on July 10th 1553. It describes a tiny, red haired girl, with sparkling hazel eyes and a bright smile. My research, however, exposed it as a fraud, written just a few years after Delaroche’s painting was bequeathed to the nation in 1902. History did not supply an image of Jane to match its power. And so the biographer, Richard Davey, invented one.

The real Jane Grey proved determined to rule as well as reign. She told her husband that she would make him a duke, but not a King. She signed documents condemning Mary as a bastard with her own hand, ‘Jane the Queen’, and raised an army to fight for her throne. Frances stayed by her daughter’s side until Mary overthrew Jane, nine days after she had entered the Tower as Queen. Frances then rode all night to beg Mary for the lives of her family, casting the blame for what had happened on the Dudleys, just as Jane would reportedly later do.

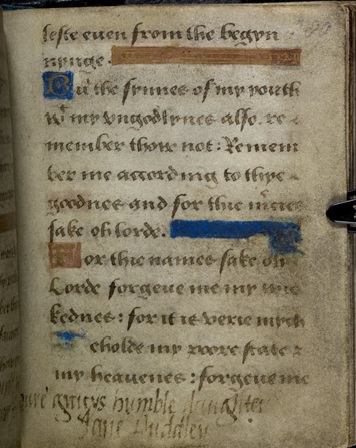

Frances might have succeeded in saving Jane’s life. But Jane, imprisoned in the Tower, continued to attack Mary’s religious policies in writing. When Jane’s father took part in a failed revolt against Mary in January 1554, she was judged a continuing threat. She refused a last opportunity to convert from her faith, and so cease to be a leader for Protestants. Instead she wrote to her thirteen-year old sister demanding she also accept martyrdom.

On February 12th Jane was escorted to the scaffold. A story that her escort included an old nurse called Ellen is today transplanted from Victorian fiction to modern biography to highlight Jane’s youth. The reality was horrific enough, with the teenager facing her bloody end ‘with more than manly courage’. Religious propagandists, anxious to distance her from her conviction for treason, now began to develop the claims that Jane was a victim of Dudley ambition. They even denied her married name. She had died calling herself Jane Dudley, but she is referred to always as Lady Jane Grey.

Over the centuries the girl who was Queen became an icon of female helplessness. The sado-masochistic appeal of this is evident Delaroche’s painting of her bound in white: the writer Nancy Mitford startlingly told Evelyn Waugh it was the source of all her adolescent sexual fantasies. Frances, meanwhile, was re-invented as Jane’s alter ego. Jane is the feminine girl, vulnerable and virginal, Frances, the mannish woman: powerful and predatory.

It is said Frances dominated her first husband, and married a twenty one year servant within weeks of his execution. A painting by Hans Eworth of the bloated Lady Dacre and her son, was, from 1727 until recent times, said to be of the couple (it illustrates a number of biographies even today). Frances in fact married a middle aged Protestant over a year later, and her actual appearance can be seen in the slender effigy on her tomb at Westminster Abbey.

Jane’s tragedy has taken on aspects of the modern misery memoir: all broken taboos, high sales and false memories. If, since the 1970s, Jane been restored some of her feisty spirit in film and biography, it is only so we can relate better to her victim status. And the message this delivers represents an old lie: it is a woman’s destiny to submit, and a man’s to rule.

The Sisters Who Would be Queen is available from:

Amazon.co.uk

Amazon.com.