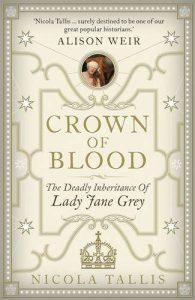

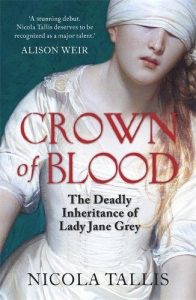

‘Crown of Blood: The Deadly Inheritance of Lady Jane Grey’ by Nicola Tallis will be published in the UK by Michael O’Mara Books on 3rd November.

Competition

To celebrate, The Lady Jane Grey Reference Guide offers you the chance to win a copy of this fascinating new biography.

Thanks to Michael O’Mara Books, one reader can win a copy in a UK give-away!

To enter:

Email me at ljgcompetition at yahoo.co.uk. Replace ‘at’ with @.

The competition ends at midnight (UK time) on Wednesday 2nd November.

The winner will be selected at random.

Good luck!

Follow Nicola Tallis on Social Media:

Nicola’s website: Nicola Tallis

Twitter: @MissNicolaTal

If you don’t win a copy, you can buy it from: