Lady Jane Dudley is summoned from Chelsea Manor to Syon

In late June/early July 1553 Lady Jane Dudley was at Chelsea Manor recovering from illness. Professor Eric Ives describes how ‘on Sunday 9 July, while she was still not well, her sister-in-law Mary Sidney arrived with a solemn and mysterious summons from the privy council to go that very night to the former protector’s mansion at Syon ‘to receive that which had been ordered by the king.’ (p.187)

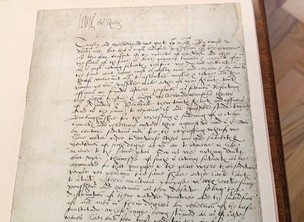

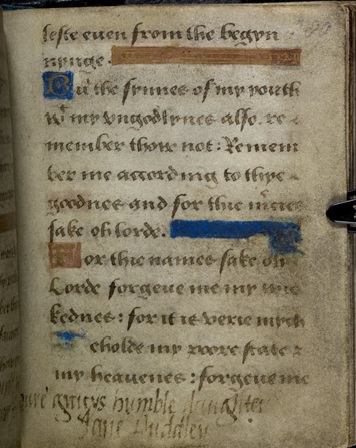

In her letter to Queen Mary, written in August 1553 Jane describes events of June/July 1553. Ives writes ‘A letter of explanation and confession to the queen is the one written appeal from Jane that would have been allowed, the August date is what one would expect, and remarks made by Mary to the imperial ambassador on the 13th indicate that she received such a letter.’ (p.19, Ives)

Jane’s letter to Queen Mary survives in 2 different versions. ‘Substantial in length – over 1,000 words in translation – it first appears in an account written in 1554 by a papal official and future cardinal, Giovanni Francesco Commendone.’ (p.18, Ives) Ives write that ‘…in 1591 a similar text attributed to Jane surfaces in the Storia Ecclesiastica della Rivoluzione d’Inghilterra…Pollini…claims to have used a text obtained from London.’ (p.18, Ives).

Two versions of Jane’s letter exist. This is how she recounts these events:

Version 1

‘After having been openly stated that there was no hope for saving the life of the King, as the Duchess of Northumberland had promised me that I could remain with my mother, after she heard that news from her husband the Duke, who was also the first person to tell me about it, she did not allow me any more to leave my house saying that when God would be pleased to call the King to his mercy, not remaining any hope of saving his life, I had immediately to proceed to the tower, as I had been made by his Majesty heir to the Crown. Which words, which caught me quite unaware, very deeply upset me, they made me wonder but much more aggrieved me. But I cared little for those words and refrained not from going to my mother, So that the Duchess got angry at her and at me also saying that is she wanted to keep me, she would also keep my husband by herself, thinking that anyway I would go to him, and really I remained two or three nights, but finally I craved permission to go to Chelsea. And there, having shortly afterwards fallen ill, the Council sent me ordering that this same night I should go to Sion to receive that which had been ordered by the King. And she who brought me this news was my sister-in-law Sedine, (Selina) daughter of the said Duke, who told me that I had forcibly to go with her, as I did.’ (p.45-46, Malfatti)

Version 2

‘For when it was publicly reported that there was no more hope of the King’s life, as the Duchess of Northumberland had before promised, that I should remain in the house with my mother, so she, having understood this soon after from her husband, who was the first that told it to me, did not wish me to leave my house, saying to me that if God should have willed to call the King to his mercy, of whose life there was no lingering hope, it would be needful for me to go immediately to the Tower, I being made by his majesty heir of his realm. Which words being spoken to me thus unexpectedly, put me in great perturbation, and greatly disturbed my mind, as yet soon after they oppressed me much more. But I, nevertheless making little account of these words, delayed to go from my mother. So that the Duchess of Northumberland was angry with me, and with the duchess my mother, saying that if she had resolved to keep me in the house, she should have kept her son, my husband near her, to whom she thought I would certainly have gone, and she would have been free of the charge of me. And in truth, I remained in her house two or three nights, but at length obtained leave to go to Chelsea, for my recreation, where soon after being sick, I was summoned by the Council, giving me to understand that I must go that same night to Sion to receive that which had been ordered for me by the King. And she who brought me this news was the lady Sidney, my sister-in-law, the daughter of the Duchess of Northumberland, who told me with extraordinary seriousness, that it was necessary for me to go with her, which I did.’ (p.497, Stone)

Location

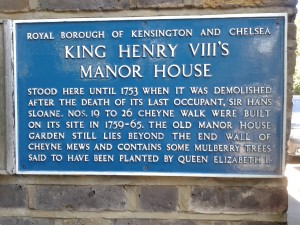

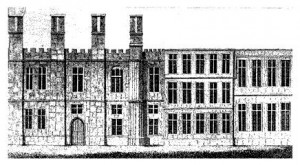

Chelsea Manor was located on what is today Cheyne Walk in central London.

Ives describes Chelsea Manor in the 16th century as ‘a fairly small royal house, on the river and noted for its knot gardens and orchards.’ (p.186-187, Ives)

‘A depiction of the north (rear) side of the Tudor Manor house, showing the 17th-century addition (right)’

From Landownership: Chelsea Manor, A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 12: Chelsea.

British History Online

Tudor History of Chelsea Manor

‘May 1536 – Henry VIII was given Chelsea Manor as part of a property exchange with Baron Sandys.

1543/4 – Granted to Queen Catherine Parr for life.

1547 – Lady Jane Grey stays at Chelsea.

1549 – Chelsea Manor reverts to the crown after the execution of Sir Thomas Seymour.

1551 – Granted to John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland by Edward VI.

1552 – Given back to Edward VI.

1553 – Once more granted to the Duke of Northumberland.

1553 June/July – Lady Jane Dudley recovers from illness at Chelsea Manor.

1553 August – Reverts to the crown after the failure to place Queen Jane on the throne.

1554 – Granted to Jane Dudley, Duchess of Northumberland for life.

1555 – Jane Dudley, Duchess of Northumberland dies at Chelsea Manor.

1557 – Anne of Cleeves dies at Chelsea Manor.

1559/60 – Granted to Anne Stanhope, Duchess of Somerset.’

From: ‘Landownership: Chelsea manor’, A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 12: Chelsea (2004), pp. 108-115. URL: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=28701

From: ‘Cheyne Walk: The Manor House, and Nos. 19-26’, Survey of London: volume 2: Chelsea, pt I (1909), pp. 65-75. URL: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=74514

De Lisle, The Sisters Who Would Be Queen.

Chelsea Manor Today

The site of Chelsea Manor today lies under numbers 19-26 Cheyne Walk in Chelsea.

Sources

Ives, E. (2009) Lady Jane Grey: A Tudor Mystery, Wiley-Blackwell.

De Lisle, L. (2010) The Sisters Who Would Be Queen: The Tragedy of Mary, Katherine and Lady Jane Grey, HarperPress.

Malfatti, C.V. (1956) The Accession Coronation and Marriage of Mary Tudor as related in four manuscripts of the Escorial, Barcelona

Stone, J.M. (1901) The History of Mary I Queen of England, Sands & Co

Landownership: Chelsea manor, A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 12: Chelsea (2004), pp. 108-115. URL: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=28701 Date accessed: 1 July 2013

Cheyne Walk: The Manor House, and Nos. 19-26, Survey of London: volume 2: Chelsea, pt I (1909), pp. 65-75. URL: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=74514 Date accessed: 1 July 2013