Matt Lewis is the author of ‘Richard Duke of York: King by Right’, ‘Henry III: The Son of Magna Carta’, ‘The Wars of the Roses: The Key Players in the Struggle for Supremacy’, ‘The Wars of the Roses in 100 Facts’ and the historical fiction, ‘Loyalty’ and ‘Honour.’

His latest book, ‘The Survival of the Princes in the Tower’ was published by The History Press in September.

To buy ‘The Survival of the Princes in the Tower’:

Follow Matt on Social Media:

Matt’s website: Matt Lewis Author

Twitter: @MattLewisAuthor

Facebook: Matt Lewis Author

Many thanks to Matt for answering my questions.

Why did you choose this subject for your book?

The fate of the two sons of King Edward IV who are remembered as the Princes in the Tower is the ultimate mystery. As someone fascinated by the period of the Wars of the Roses, and by Richard III in particular, the Princes in the Tower are woven deep into the fabric of that era and our understanding of it. It defies resolution 500 years after the event, yet I wondered how well we really knew the story. Strip away the Shakespearean malevolence and the sensationalism of earlier Tudor writers and how much of what has been passed to us will be left? Often, the original, contemporary sources can tell a very different story to the tales that swell with elaboration and exaggeration as the years, decades and centuries pass.

What does your book add to existing works about the Princes in the Tower?

I really wanted to examine the idea that the boys were not murdered at all in 1483. The traditional argument always centres around who was responsible for their deaths in the summer of 1483. Occasional lip service is paid to the notion that one or both of them might have survived and there are books on Perkin Warbeck which necessarily examine the idea of Richard’s survival, but I don’t think this side of the story has had a proper telling before. The traditional accounts all have serious problems for me, which are detailed in the early chapters of the book, and I think the possibility of their survival is too quickly dismissed.

What surprised you most researching this book?

The real shock is the stories presented by the contemporary writers that are largely ignored. The utter lack of conviction held by anyone as to what happened gives the lie to More and Vergil’s apparent certainty. Before and after them, writers recorded various stories, including that both boys had been safely removed from the Tower. The blind poet Bernard André, who acted as tutor to Prince Arthur Tudor, clearly wrote a very different version of what is remembered as the Lambert Simnel Affair. André insisted that the boy in Ireland claimed to be a son of Edward IV named Edward. That can only be Edward V. He also asserted that several messengers were sent to Ireland to identify the boy and all returned confirming that he was who he claimed to be. Did this version escape the Tudor myth building that followed? It would make sense of Elizabeth Woodville’s sudden fall, her son Thomas’s swift imprisonment and the destruction of the record of the Irish Parliament of 1487 that Henry VII ordered. The real surprise was just how much of what we think we know comes from unreliable, later, Tudor sources that are at odds with what was written at the time.

If the Princes died, who do you think is most likely responsible for their deaths?

Undoubtedly Richard III would be the prime suspect. If the police were investigating this now, his would be the first door they would knock on. He was responsible for the boys’ care and made no fuss about their disappearance. Of course, if they didn’t die and Richard had ensured they were safely provided for out of the way of London and the court, then he had no reason to make a fuss.

Do you think that Edward V fought and died at the battle of Stoke Field? What is the evidence for this?

The more I study this and consider it, the more likely I think it is that the Lambert Simnel Affair was a rebellion in favour of Edward V, not Edward, Earl of Warwick. The fact that they shared a name and that Warwick was in Henry VII’s custody perhaps offered a convenient way to negate the threat, to make it a joke. Apart from André’s about the identity of the boy in Ireland, there is a great deal of confusion in the sources about the age of the boy involved. Vergil changed the Latin word used to describe him from ‘puer’ to ‘adolens’, suggesting he was older than Vergil was initially led to believe. It is the only real way to make sense of what happened to Elizabeth Woodville and Thomas Grey, though it remains frustratingly unproven.

There are other bits of suggestive evidence in the book, but one story I really like is from the Book of Howth, an Irish chronicle. It tells how Henry VII summoned all the Irish lords to England in the wake of their support for Lambert Simnel. He is said to have quipped that the Irish lords would crown an ape one day to try and unseat him. He then sent the boy captured at Stoke Field out to serve wine to the lords to demonstrate how far he had fallen. None of the lords recognised him. The only one who had not attended the coronation in Dublin was the Lord of Howth himself who, when Henry was forced to tell everyone that this was their ‘king’, called for him to pour him some wine. I wonder whether Henry wasn’t profoundly unnerved by their failure to recognise the lad. If the story is true, of course.

Why was ‘Perkin Warbeck’ such a threat to Henry VII?

Perkin posed such a terrifying threat to Henry simply because no one, including Henry, really knew what had happened to either of the Princes in the Tower. If Stoke Field had led to Edward V’s capture, there was still one prince of the House of York unaccounted for. It should not be forgotten that wider European politics were heavily at play here too. Foreign monarchs had much to gain from unsettling an increasingly powerful and confident England. Nevertheless, backing an imposter was something most kings and emperors would consider beneath them. It is important to remember that a pretender (from the French word, meaning to claim) was different to an imposter. The affront to royal dignity of treating a commoner as an equal would have been abhorrent to European monarchs.

Whatever the truth of his origins, Perkin appears to have genuinely convinced many. His English was flawless, despite his eventual confession insisting he had been forced to learn English in his late teens. Frankly, that’s patently nonsense. At the moment, it remains impossible to prove whether Perkin really was Richard of England, as he called himself, but it is clear that Henry VII and his government were genuinely terrified by his appearance and prolonged threat. That can only mean that even they, ten years and more into Henry’s reign, could not be sure that at least one of the Princes in the Tower wasn’t still alive and at large. If they couldn’t be certain, how can we?

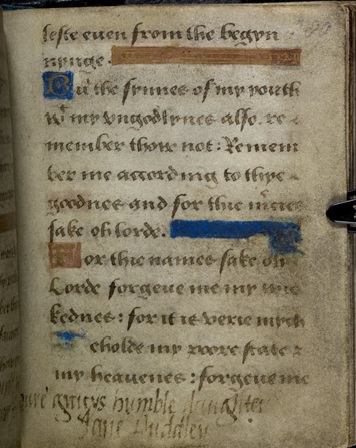

Do you think there is any truth to the theory that Guildford Dudley (through his mother) was a Yorkist heir?

I would love this to be true, not least for the later implications around Elizabeth I and Robert Dudley. As with so many other aspects of this story, the evidence is circumstantial and always requires a leap of faith, but it is compelling. Why was Jane Guildford, his mother, described on her tomb as a princess? In what way was she a princess, and how did it slip past the authorities that she was described thus? Why is she buried in Sir Thomas More’s chapel in Chelsea? What do the links to More mean? Contemporary reports suggest that it was Jane who was adamant her son Guildford should be declared king alongside Jane Grey, not that he should merely be her consort. Where did she get such an outrageous idea from? Unless her father held a secret in his blood that made Guildford’s claim arguably better than Jane Grey’s. It’s an intriguing idea that, for now at least, lingers just beyond definitive proof.