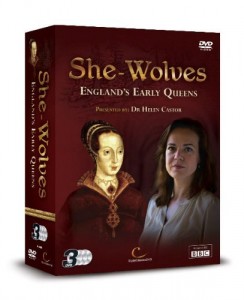

Dr Helen Castor is the author of ‘She-Wolves: The Women Who Ruled England Before Elizabeth’ and ‘Blood and Roses.’

Both ‘The Sunday Times’ and ‘The Independent’ have named ‘She-Wolves’ as one of their history books of the year.

Many thanks to Helen for answering my questions.

Why did you choose this subject for your book?

The twin preoccupations of my work have always been power and people. It’s easy to take for granted that rulers rule, but I’m interested in how they do it and why people obey them. And I’m fascinated by the complex and contradictory ways in which human beings respond to environment and circumstance.

Those two interests coalesced when I began to think about Edward VI’s death in 1553. Because we know how the story turned out, I think we often tend to overlook just how unprecedented and alarming a moment this was. All his possible heirs were women, so that, amid all the uncertainty, the one unavoidable fact was that for the first time England was about to experience the rule of a female sovereign. And that made me want to go back and examine England’s experience of female power in the centuries leading up to that moment.

What does your book add to previous works covering these queens?

There are some parts of the story where I’ve come to different conclusions in matters of detail – I haven’t seen anywhere else, for example, the suggestion that Eleanor of Aquitaine engineered her own divorce in quite the way I’m proposing here – but overall I hope it asks slightly different questions.

There’s a tendency, I think, in writing about female subjects so long ago (and perhaps also not so long ago) to fill in gaps or create explanations by focusing on the possible contours of their emotional lives. I wanted to allow full play to their political roles and the power structures within which they acted, so that, for example, Matilda’s failure to secure the crown can be explained not by the fact that she was ‘too haughty’, but by the circumstances that gave rise to that accusation: that a woman trying to act as a king was seen as unnaturally domineering rather than regally commanding. I also hope that the book gives an interesting perspective on the place of these queens within a political culture as it developed over five hundred years, when the great historiographical divide of 1485 means that medievalists and Tudor historians often don’t communicate as constructively as they might.

Out of Matilda, Eleanor, Isabella, Margaret and Mary, who was easiest to write about?

None of them! I don’t find writing easy, ever.

Which Queen do you admire the most?

I admire all of them, in different ways. It’s hard not to be awestruck by Eleanor of Aquitaine, because she was simply so extraordinary. Not many people get to be queen of France and queen of England, go on crusade, play a pivotal role in European politics for decades despite giving birth to ten children and enduring fifteen years of imprisonment, and cross the Pyrenees for the last time at the age of 76. But I suppose I have a great deal of admiration for Matilda, who really did attempt to tread an unprecedented political path, and came extremely close to succeeding.

Which Queen do you think faced the most difficult challenge?

It depends what kind of difficulty we’re talking about. Matilda’s was the most intractable political dilemma, I’d say – trying to be a king when being a king and being a woman were implicitly understood to be mutually exclusive. But Matilda fought and won a victory of a kind, when her son became king as Henry II. It’s another kind of challenge altogether to contemplate what Margaret of Anjou faced, having devoted her whole life to defending her son and his inheritance, only to lose him and everything she had fought for when he was just 17, in his first experience of combat.

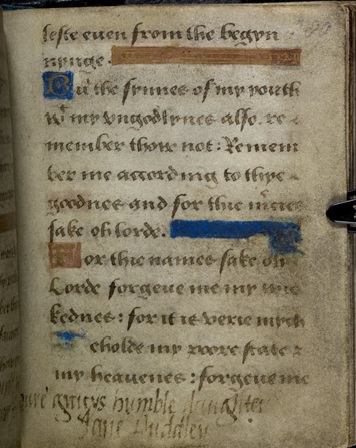

You use the recently discovered ‘Streatham’ portrait previously on display at the National Portrait Gallery to illustrate Lady Jane Grey. Why did you choose this portrait over the Teerlinc (Yale) miniature?

Because I’m not convinced that the Teerlinc miniature is Lady Jane. It would be wonderful if we had an equivalent for Jane of William Scrots’s wonderful portrait of the teenage Elizabeth – but, in the absence of that, the Streatham picture seems currently to be the most plausible illustration of Jane’s image (albeit not a portrait from life).

In the ‘Note on Sources and Further Reading’ you state that your conclusions (regarding the 1553 succession) differ from those of Professor Eric Ives. In what way do they differ?

Well, I’m thinking particularly of Professor Ives’s suggestion that Mary’s challenge for the throne in 1553 should be seen as a rebellion against an incumbent ruler – Jane – whose regime held all the cards, politically and militarily. It’s a fascinating argument made by a historian I admire enormously, and one which does a huge service in making us re-examine all our assumptions about the crisis. But ultimately I can’t see Jane’s short-lived regime in that way because the one card it lacked, crucially, was the one without which political security couldn’t be achieved: legitimacy. As it happens I also don’t agree with Professor Ives that Jane’s claim was validated by the principles of the common law (both because the crown had never straightforwardly descended by those principles, and because of the sidestepping of her mother’s claim); but the crucial factor – in the sixteenth just as in previous centuries – was whether a regime could muster enough support across the country as a whole to sustain a government that had no police force and no standing army to enforce its will. It might have seemed, from inside the council chamber in July 1553, that Jane’s regime was politically viable; but from the moment her proclamation was greeted by silence it began to become clear how great a misjudgement that was. In other words, the course of events themselves, and not just history written by the winners, demonstrates that legitimacy, as perceived by her subjects, lay with Mary.

The description you give of Queen Jane is based on the only contemporary account by Baptista Spinola. In the paperback version of her book ‘The Sisters Who Would Be Queen’ (published 2010); Leanda de Lisle argues that the letter and description are a fake. Do you have an opinion about this?

I finished writing She-Wolves at the end of 2009, and by the time I read Leanda de Lisle’s argument my book was already in proof. I do find it convincing – frustrating though it is to have this glimpse of Jane snatched away! It’s also salutary to be reminded how important it is to re-examine the ‘canon’ of evidence piece by piece. I was conscious of that often in writing about the 1550s using the Calendars of State Papers – wonderful sources, but I was so often aware that I was using a translation without sight of the original, which is a deeply unnerving process. I wasn’t able to go back to the original texts for this book, but I hope to in the future.

How seriously do you think Mary considered naming Margaret Douglas as her heir, given that Mary’s victory over Jane had set a precedent?

I’m sure that, in some ways, Mary would have loved to name Margaret Douglas as her heir, rather than the heretic bastard Elizabeth. But she was an intelligent enough politician, I think, to know that the plan was a non-starter. The same circumstances that had swept her to the throne instead of Jane Grey would apply to any contest between Elizabeth and Margaret Douglas. And I also think Mary was enough her father’s daughter to see the force of the argument that his blood not only would but should prevail.

In fact, one of the remarkable things about Mary, I think, is the extent to which she was able to live in hope, even after all the reverses she had suffered. Hope (as well as determination) was there in her self-assertion in 1553; it was there in her marriage and her belief that she would give birth to an heir; and maybe she was also able to hold on to the hope that Elizabeth’s acquiescence in the restoration of Catholicism might be more than politic and superficial.

You end with the question, ‘We are left to wonder: would Matilda – who was, unlike Elizabeth, the mother as well as the daughter of a great King Henry – have exchanged her son’s inheritance for the crown she never wore?’ (p 448). What is your view?

The two things every monarch wanted were power, and to pass that power on to a direct heir. Elizabeth achieved the first, and Matilda the second. I suppose my view is how profoundly this demonstrates the difficulty for a woman of operating in a situation where the ‘neutral’ position is male: she simply can’t do or have it all.