Historian Leanda de Lisle has very kindly written this guest article. The paperback of the best selling, ‘Tudor: The Family Story’ is published on Thursday 5th June.

A renaissance-hunting scene opens Trevor Nunn’s 1985 film, Lady Jane. Amongst the white clad riders is Frances, mother of the future Nine Day’s Queen. When the doe is brought to bay, Frances dismounts. Soon a river of blood will run on the snow. The scene captures her historical reputation as a destroyer of innocents and foreshadows Jane’s fate. But history has traduced Frances and buried the real life of Lady Jane Grey.

Frances was Henry VIII’s niece and the wife of Harry Grey, Marques of Dorset. Under the terms of the late King’s will her daughters followed Mary and Elizabeth Tudor, half sisters of Henry’s son, Edward VI, in line to the throne. But it was expected that young Edward would one day marry. Harry Grey pursued the hope that it would be to the eldest Grey girl, Jane. It is Frances, nevertheless, who is credited with being the dominant force in the family, and one whose ambition would destroy Jane. She was, historian Alison Weir tells, ‘greedy for power and riches’, ruling ‘her husband and daughters tyrannically and, in the case of the latter, often cruelly’.

The accusations of child abuse originate in the same story that fuelled later claims that Frances was a bloodthirsty huntress. Over a decade after Jane had died the academic, Roger Ascham, described finding the thirteen-year old prodigy reading Plato in Greek, while the rest of the household was out hunting. Hunting was then considered a noble and practical pursuit, supplying a house with food and skins. There was nothing exceptional in Frances being amongst them. More damning is that Ascham also recalled Jane explaining that she loved to study because lessons with her kindly tutor were a respite from ‘sharp, severe parents’. Ascham was, however, writing to an agenda: his desire to overturn harsh contemporary teaching methods. At the time he met Jane he had commented only on her parents’ pride in her work, and the ‘kindly’ tutor was busy expressing a desire to ‘bridle’ a spirited teenager.

Tales of Frances’s exceptional cruelty don’t bear close examination. But what of the further accusation that she drove Jane to her death through greed and ambition?

By the summer of 1553, when Jane was sixteen, it was evident Edward VI was dying. Anxious that his Catholic half sister, Mary Tudor, should not undo his religious reforms, he had written a will excluding his sisters from the succession on grounds of their illegitimacy (the marriages of their mothers to his father having been annulled). In their place he named the passionately Protestant Jane. That Jane was now to be a Queen regnant was not an outcome that Frances had sought. Her own claim to the throne was superior to her daughter’s under the usual rules of inheritance. Frances was, rather, obliged to accept the King’s decision: one likely inspired by Edward’s judgement that Jane was more likely than she to produce a male heir.

As a mark of submission Frances carried her daughter’s train in the procession to the Tower, where Jane was proclaimed Queen on July 10th 1553. The additional and famous description of Jane, tiny, red-haired, and smiling, said to have been written by a contemporary witness, is, I can reveal, a twentieth century fraud.

Frances remained with her daughter while a determined Jane raised an army to fight for her throne against Mary Tudor. And, when Jane was overthrown nine days later, it was Frances who rode all night to see Mary and beg for the lives of her family. It was through no fault of her own that Frances’s efforts came to nothing. Jane continued to attack Mary’s religious policies even while a prisoner. And when Harry Grey took part in a failed revolt against Mary in January 1554, Jane was judged a continuing threat.

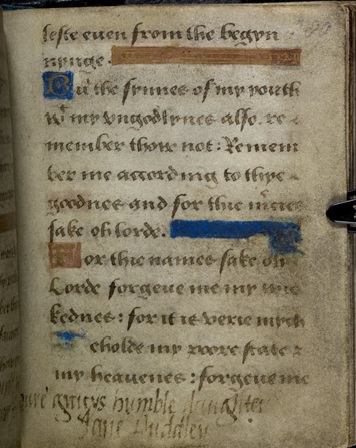

On the scaffold, aware that the Protestant cause was being tainted by treason, Jane’s last speech reminded people that while she was guilty in law, she had accepted the crown she was bequeathed and was innocent of having sought it. She was beheaded on February 12th dying, it was said, ‘with more than manly courage’. Religious propagandists later developed Jane’s clams to innocence and over the centuries the girl who had held all the power of a Tudor monarch, became an icon of female helplessness. The sado-masochistic dimension to this is evident in Paul Delaroche’s 1833 historical portrait, ‘The Execution of Lady Jane Grey’, now at the centre of a major exhibition at the National Gallery. Jane dressed in white, feeling blindly for the block, has all the erotic overtones of a virgin sacrifice.

Frances, meanwhile, was re-invented as Jane’s alter ego: powerful, ruthless, and sexually predatory. A double portrait of Lady Dacre and her son by Hans Eworth was, from 1727, said to depict Frances and a twenty one year old boy she married within weeks of her husband’s execution. In fact Frances married the middle-aged Adrian Stokes a year later. The revelation of the true identity of the Eworth sitters, in the 1980s, has not prevented Jane’s biographers from continuing to use the image of Lady Dacre to claim a resemblance between Frances and Henry VIII.

This urge to associate powerful women with masculine characteristics is an ancient one, and has fuelled the caricature of Frances the bloodthirsty huntress. Unlike reading, bridling a galloping horse does not well reflect the passive, gentle nature traditionally expected of women. The good girl is always the weak doe. The wicked woman holds the reins of power. That is the moral of the spun history of Lady Jane Grey and her mother. Strange we remain so willing to accept it.