Elizabeth Fremantle is the author of ‘Queen’s Gambit.’

‘Queen’s Gambit’ is available to buy now in the UK and will be published in the US in August.

To buy her new novel:

Elizabeth Fremantle – Queen’s Gambit

Penguin Books

Follow Elizabeth Fremantle on Social Media:

Elizabeth’s website: www.elizabethfremantle.com

Twitter: @lizfremantle

Facebook: Elizabeth Fremantle

Many thanks to Elizabeth for answering my questions.

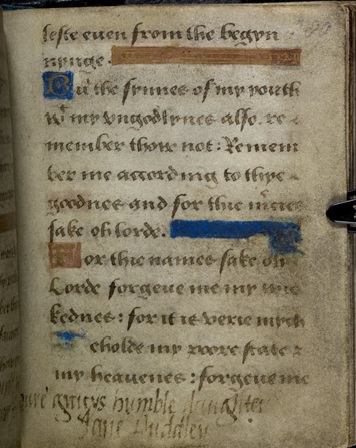

Why did you choose to write about Katherine Parr?

I was drawn to Katherine initially, some time before I had ever thought of writing historical fiction, because she is one of the earliest English female writers and I have long been interested in the womens’ voices that began to emerge in the early modern period. I was intrigued too by the fact that though she was the wife who ‘survived’ Henry VIII (no mean feat) she seemed to come across as somewhat meek and uninteresting. I suppose this was why she was largely overlooked by many fiction writers whose appetite for the stories of Henry’s other, seemingly more glamorous, wives has been insatiable. When I began to research Katherine Parr in earnest, I came to see that her story was far from dull, that she was an astute political player who trod the knife-edge of court intrigue and stood up for religious reform at great personal risk. But more than that, her story was human and though she was admirably shrewd and strong she was also flawed, making a disastrous decision in the name of love. Indeed her attraction for me, lies in her unfathomable contradictions.

Did the fact that Katherine Parr is one of Henry’s lesser known wives make it easier or harder to characterise her?

The fact that she one of the more obscure wives was certainly a driving force in my fascination, as I generally find myself drawn to the less well-known stories of history. Many talented writers have tackled the other wives and unless I felt had something new or important to say about a very famous historical figure, I would feel less compelled to fictionalise them.

In the novel, did Katherine have more freedom to be herself as Henry’s wife, (in the beginning at least, when she published ‘Prayers or Meditations’, voiced her opinions, read and discussed religious books with her ladies and was Regent), than she did when married to Thomas Seymour?

The way I have seen it is that though she had a good deal of influence during the early period of her marriage to the King, and was seemingly at liberty to voice her views, it always held a level of risk, which was bourn out by later events. Even during her Regency her power was mediated through Henry and she was careful to make her first book Prayers or Meditations uncontroversial; it wasn’t until after Henry’s death that she published the outwardly reformist Lamentation of a Sinner. As dowager her faith was not under scrutiny and the regime was in tune with her own beliefs, so she was not under the constant threat that coloured her queenship. Her marriage to Seymour however, raised other, different concerns and perhaps more hidden threats.

Out of Katherine Parr’s inner circle of ladies, who did you enjoy writing about the most?

Anne Stanhope – I’m afraid I have made her rather a figure of hate in line with the opinion of many male historians and perhaps this was not entirely the case in reality; it is hard to know the truth in cases like this. She was an intriguing figure and worked as a complex adversary for Katherine as they shared political and religious sympathies but were adversaries. If I’d had the space I would have expanded on her story and I couldn’t resist her making a reappearance in my next novel.

Through Dr Huicke we learn the truth about an incident witnessed by Katherine involving Thomas Seymour and a dropped tray of tarts. Other than as witnesses to events, why did you make Dr Huicke and Dot Fownten major characters?

Both Dot and Huicke do indeed bear witness to many important events but that is not their sole function in the narrative. With Dot I wanted to tell another story about the forgotten people who oiled the wheels of court life – the hundreds of souls who served the nobility. Her story is about loyalty and the powerlessness of illiteracy, and also is a way of showing the kinds of relationships women of different classes had with one another in the period and the close proximity in which they lived. In Dot’s case I was able to explore the opportunities for social mobility the court offered and also the notion of a happy marriage.

Huicke is differently conceived, in that it is well documented (whether true or not) that a royal physician informed Katherine of the warrant for her arrest signed by the King. This is an event upon which a plot strand turns and from it sprang a character whose loyalty was such that he would risk his life to support hers. I felt strongly that I wanted to demonstrate the kind of friendship that was not characterised by sexual attraction and so in my mind it was an obvious leap of the imagination that Huicke might be homosexual. This is entirely of my imagination and some might feel I have taken liberties with a ‘real’ figure, but I felt it was one way of creating a world in which the things that have gone unsaid in history could be envisaged as a ‘normal’ part of the social landscape. I like to think he stands in for those homosexual men who must have existed but whose stories have been suppressed.

Your portrayal of Princess Elizabeth is not very sympathetic. Why?

I’m interested that you see it that way. I suppose this is because much of Elizabeth’s story comes from Dot’s perspective and Dot is essentially eaten away with jealousy as she watches Elizabeth draw her beloved Meg under her spell only to cast her aside. Katherine however adored her. To me she was a precocious child who had lived through extreme difficulty – her mother executed and reviled, she was the adored daughter one day and the illegitimate outcast the next, consequently learning early about the world’s ruthlessness. I came to understand Elizabeth as someone who polarised opinion. There is a scene between Elizabeth and Jane Grey in which she tries to explain the way that she sabotages the things dearest to her and how she feels in the grip of a force she doesn’t understand. She is complex, clever, tricky, never for a moment dull and grows up to be an extraordinary woman, but learns at an early age that the desire to be liked does not sit comfortably with the desire to hold onto power.

Towards the end of the novel you have Levina Teerlinc ‘paint a likeness of Jane’ for King Edward (p.432). Do you think that the ‘Yale’ miniature of a young woman by Teerlinc is of Lady Jane Grey?

This is interesting to me because Levina Teerlinc is a main character in my new novel. I am undecided about the Yale portrait. There appears to be some confusion about the symbols of the oak leaves and gillyflowers she wears. But Levina Teerlinc did paint Jane’s sister Catherine Grey at least twice so it is not beyond the realms of the imagination to assume she also painted Jane at some time. For the purposes of my novel I have intertwined the stories’ of the Grey girls with that of Levina Teerlinc and have built on the existence of the Catherine Grey images to support this idea. In my imagination Jane Grey looks more like her mother Frances Brandon, so darker, with finer features, which would be more in tune with the Syon portrait. But this is conjecture – as a novelist I have to take a position in a way an historian should avoid. I need to create a firm physical character in my mind and when we know little about how a person looked (or in the case of Jane Grey have only one unreliable description of her and no definitive portrait) then her looks come from her character. It is all a grey area – forgive the pun.

Did you plan a trilogy from the beginning? Can you tell us any details about the second novel?

It was always a trilogy but thematically so, rather than carrying on following the protagonists’ lives, the background of the succession and the political climate provides the continuum and the focus moves on in time and onto other characters. The next book, which I am calling either Queen Jane’s Shadow or House of Queens, focuses on Jane Grey’s two younger sisters Catherine and Mary, two girls dangerously full of Tudor blood and buffeted by the politics of their time. Catherine is a capricious and immature girl who becomes devastatingly caught up in her own, largely narcissistic, notions of love, which lead to her downfall. Mary is a four-foot hunchback and as such has a unique perspective, as both insider and outsider, on the court, and so she becomes a pivotal cog in the narrative. Her own surprising romantic story is not without controversy either. Levina Teerlinc helps the girls survive the treacherous times of Mary Tudor’s bloody reign but it is when Elizabeth comes to the throne that things become increasingly complicated for the Greys.