Sarah Gristwood is the author of ‘Arbella: England’s Lost Queen’, ‘Elizabeth and Leicester’ and ‘Blood Sisters: The Women Behind the Wars of the Roses.’

Many thanks to Sarah for answering my questions.

What does your book add to previous works covering these women?

I think – hope! – that by linking them together it gives some sort of context. Their individual stories are so exceptionally dramatic, and so patchily documented, that they can provoke almost a kind of incredulity. But by putting them together, and showing how their lives echoed and interrelated with each other’s, it’s possible to give a more rounded picture.

You write that ‘these women should be a legend, a byword.’ (p.8) Why do you think they are less well known than their Tudor counterparts?

Largely because of that lack of evidence, about some crucial aspects of and episodes in their lives. In fact, of course, we tend not to have, from this period the kind of letters that give an aristocratic woman’s feelings, or a man’s either – the Paston letters being the great exception that proves the rule. And maybe, just maybe, some of these women were doing things that didn’t sit very easily with the men who have mostly written their histories.

Which woman did you enjoy writing about the most?

Probably Margaret of Burgundy (Margaret of York) – sister to Edward IV and Richard III. Partly because she has in some ways left a more visisble legacy of works and images. Partly because to me she came over very likeably – though since she sent Perkin Warbeck and Lambert Simnel against him, I’m not sure Henry VII would agree!

Why do you think that Cecily Neville has been so overlooked?

Cecily Neville is the one woman of the seven I cover who’s never had her own biography as such, and that’s probably because no biographer could work around the fact that we don’t know where she stood over her son Edward’s decision to execute his brother Clarence, or her third son Richard’s decision to take her grandson’s throne. It’s really frustrating – she’s obviously a forceful character, and we do know some fascinating detail about her, but not where she stood over these crucial conflicts that must have torn her family apart.

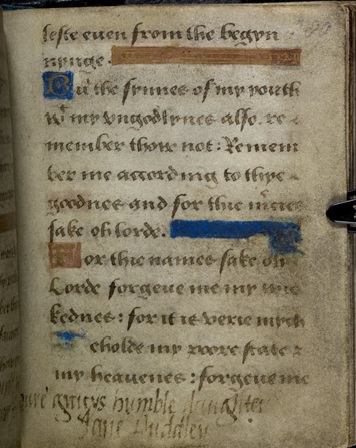

You quote Arthur Kincaid that ‘Elizabeth in her letter was referring to a hoped-for marriage – though not necessarily with the king.’ (p227) If the letter was written by Elizabeth of York, do you think that she was referring to Richard III or the Duke of Beja?

I don’t think we can know, and I’m wary of theorising ahead of the data – especially on anything to do with Richard III. And Kincaid’s work threw up a good many questions about that letter in its entirety.

What do you think the legacy of the Blood Sisters was?

Collectively their main legacy was dynastic. Genetic – and I noted with interest that the DNA strand used to identify Richard III’s bones derived from his mother Cecily. Elizabeth of York (like Cecily Neville, and Elizabeth Woodville, and Margaret Beaufort) was ancestor to every monarch of this country from Henry VIII to today. But I wanted to ask also in what other sense they might have paved the way for that great female ruler who came in so shortly after them, Elizabeth I. And I believe their strength and determination – even Marguerite of Anjou’s determined bid for power – does represent another sort of legacy.