Kelcey Wilson-Lee is the author of ‘Daughters of Chivalry: The Forgotten Children of Edward I’ which was published in March by Picador.

Buy ‘Daughters of Chivalry’:

Follow Kelcey on Social Media:

Kelcey’s website: Kelcey Wilson-Lee

Twitter: @kwilsonlee

Many thanks to Kelcey for answering my questions.

Why did you choose this subject for your book?

I have long studied medieval women and been frustrated by the persistent popular notion that women living in this period were powerless pawns. Their world was undoubtedly deeply patriarchal and at times openly misogynist, and even elite women faced real legal and practical limitations on their ability to be self-determining and influential, but some women – through determination or cunning – managed to carve their own paths, to safeguard and promote their children, to wield considerable influence and even authority in their time.

For a historian trying to convey the complexity and nuance of historic women’s relationships with power, what better archetype to overturn than that of powerless princess stuck in a tower? So I set about learning about the princesses of medieval England, and in doing so stumbled upon these five fabulous sisters and the stories of their lives – largely lived at court, unusually well recorded, and with some truly extraordinary episodes. Once I’d found them, I had to tell their stories.

What does your book add to the existing works about the daughters of Edward I?

The past two decades have seen an explosion in both academic and popular studies of England’s queens, but there have been very few studies of their daughters. No one had written a significant historical work about the daughters of Edward I and Eleanor of Castile since Mary Anne Everett Green’s wonderful Lives of the Princesses, in the mid-nineteenth century. This superlative work – far advanced for its day in the use of primary historical sources – is brilliant and a must-read for anyone seriously interested in the lives of royal women, but its format of mini-biographies and the style of writing of that vintage didn’t allow for lots of interpretation contextualised within the broader world the women inhabited, nor did it enable us to consider closely the relationships between the women, which I find really interesting. I hope that Daughters of Chivalry has contributed these elements, while bringing these women’s lives to new readers.

Which daughter was the most difficult to write about?

Early in my work, I found Margaret, who grew up to be Duchess of Brabant in the Low Countries, the hardest daughter to write about. Margaret was the most conventional child – her interests were what ladies were supposed to be interested in, her behaviour was flawless for the time – in rather stark contrast to some of her sisters, who were rather more rebellious or seemingly individual. Initially, I struggled to make sense of this conventionality; was Margaret just boring or lacking personality, I wondered. As I learned more about Margaret, however, I realised her behaviour had real purpose and actually led to her being a very successful consort and royal daughter. This allowed me to make sense of her earlier life, and hopefully give her some shape as a real person.

What surprised you most researching this book?

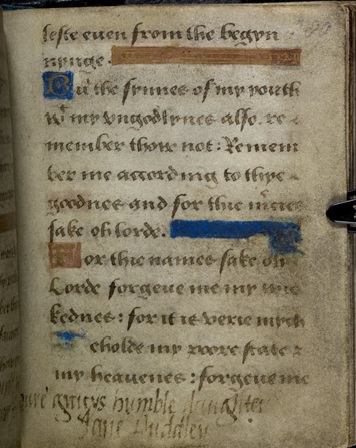

I was most surprised (and delighted!) by how much information about the real personalities of these women survives – tucked away in manuscripts held by the British Library and scrolls at the National Archives are details about the favourite childhood sweets princesses who have been dead for seven centuries. We can see them visiting their siblings, learn the names of their riding horses, wonder at why they loved sequins so much (not really – everyone loves sequins because they’re amazing!). We can read letters they wrote to their father and to their brother, chatting about popular music and unpicking international diplomatic incidents. These women barely show up in the major chronicle sources, and that intimidated me at first, but so much remains in contemporary records that attest to them as individual people and also to what they thought their roles were as princesses of England.

Which of Edward’s daughters did you find the most interesting to write about?

I loved writing about Eleanora, the would-be queen who spent her life in a kind-of self-imposed monarchical apprenticeship from which she never graduated. Her ambition, determination, and sense of duty, I found inspiring. But for the sheer pleasure of thrusting one’s fist upward in the air and shouting ‘Yes!’, I will say Joanna was the most fun to write about. Perhaps if one had met her, she might not have been the easiest to get along with, but Joanna of Acre displayed an infectious boldness throughout her life, and in the restricted environment in which she and all contemporary women lived, her refusal to be cowed is all the more exciting and commendable.

Who do you think was most successful in fulfilling her role as daughter of the king?

Most of the sisters were successful in their own ways as adults. Eleanora tried the hardest to be what her father needed, but she was constrained by fate. Elizabeth did her duty as a royal daughter in marrying abroad to a man of use to England, younger than any of her sisters, but the experience almost broke her. In the long run, probably Margaret was the most successful – in part through luck (she had the best marriage of her siblings), in part through her steady practice of intercession, which brought much-needed military support to her father’s wars and won favourable trading conditions to sell England’s most important and valuable export, wool.

‘And history did not favour lasting influence for the sisters of English kings.’ (p.280). How much favour did the sisters lose when their brother, Edward became king?

Edward I’s own two sisters died within two years of his ascension to the throne. His father Henry III had three sisters, two of whom died when they were all fairly young and the third of whom (Eleanor) eloped with Simon de Montfort, who led a rebellion against Henry; at the apex of the Baronial War, Eleanor held Dover Castle against her brother’s forces and was ultimately exiled from England. Therefore, when Edward II became king there weren’t any recent examples of king’s sisters having positive, impactful relationships with the Crown.

Ultimately, precedent may not have mattered, since nothing about Edward II’s reign seemed to follow precedent. Even before he became king, Edward of Caernarfon openly eschewed the advice of his family and the usual chief magnates, instead preferring to listen to his close personal companions, some of whom were incredibly unpopular. Edward’s clear disregard for established protocol meant that his sisters lost influence not only insofar as they held it personally under their father as ‘daughter of the king’, but also insofar as they were leading noblewomen through marriages to men whom, under a more typical king, will have expected to have greater sway than they felt under Edward. One result of Edward’s style of kingship was that his sisters and their progeny either faded from England’s central base or – in the case of Joanna’s children – were nearly destroyed entirely.