Although Lady Jane has featured in historical documentaries such as ‘She – Wolves: England’s Early Queens’ and ‘Bloody Tales of the Tower’, ‘England’s Forgotten Queen: The Life and Death of Lady Jane Grey’ is the first that focuses on Jane.

Presented by Helen Castor, it also features ‘Jane’ historians, Leanda de Lisle and J Stephan Edwards.

The assistant producer (Lucie Crawford) got in touch to say she had been using my website and I met with her to discuss Jane. I also answered questions and suggested sources throughout the summer.

What was wonderful about the programme was the chance to hear about all the new developments about Jane over the last 10 years and to view documents that relate to Jane and her nine days as Queen.

Episode 3 – Jane’s power base dissolves into deceit and treachery. The question remains, will she escape with her life or will she pay the ultimate price for her part in the coup?

17th July

Stephan Edwards – Once the Privy Council had to be locked in the Tower, Jane was intelligent enough to know that she was in serious trouble.

Helen Castor – Northumberland arrived in Cambridge on 15th. Here, he hesitated and waited for reinforcements.

Saul David – Reinforcements coming in, artillery. Assumes Mary will be entrenched at Framlingham. Now ready to move, 3000 strong.

Helen Castor – He doesn’t know that the warships have mutinied. Northumberland is outgunned but he doesn’t know it yet.

News has reached the Privy Council in London and they haven’t told Northumberland.

18th July

Helen Castor – Northumberland begins to move towards Framlingham.

There are rumours that the treasurer of the Royal Mint, had mustered troops for Mary.

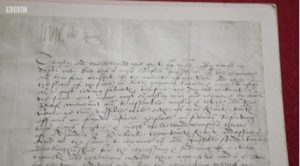

Jane begins writing to powerful land owners for help. Letter written 18th July 1553 by Jane.

Helen Castor – Letter asking for help in subduing the violence that is taking place in her kingdom. Last ditch attempt by Jane to rally support behind her.

A message is sent to the Duke of Northumberland from the Tower.

Saul David – He learns he is outnumbered and out gunned. At this point he makes what we can say in retrospect is the fatal decision to withdraw back to Cambridge.

Helen Castor – Abandoned by the Privy Council, time has run out for Queen Jane. The 18th of July would be the last day of Jane’s nine day reign.

19th July

Helen Castor – Only those closest to Jane remain with her in the Tower. Privy Council make Northumberland the scapegoat. The Privy Council proclaim Mary at Cheapside and the City erupted in celebrations.

Nicola Tallis – The reaction is one of complete elation. Everyone is completely overjoyed that she has at last come into her birth right. John Stowe, records there were bonfires, dancing, the Te Deum was sung, wine flowing through the streets.

Helen Castor – From this moment on, Northumberland was the instigator of the coup, he was the man driven by ambition. The bully, the tyrant, the traitor. History is written by the winners.

Leanda de Lisle – Privy Council sent military force to the Tower to tell her father that Jane was no longer Queen and that Mary had been proclaimed. They weren’t sure how he would react. He simply said ‘I am just one man.’ There was nothing he could do to defend his daughter’s rights as Queen any longer and he went to tell her that she was no longer Queen.

Helen Castor – Pope’s envoy described the scene. Jane had not chosen to take the crown.

Stephan Edwards – Jane said, can I go home now? It is almost as though she has had to put on this persona of a Queen and play the role for several days.

Helen Castor – A young women who has found the strength to inhabit that role for nine days in a situation of such stress and crisis and then suddenly displaying the naivety to think that there was any chance that she might be allowed to do home.

Stephan Edwards – That almost makes us wonder, if she is so intelligent, it’s almost as though she lost all of that for a moment.

Leanda de Lisle – Jane is stripped of her valuables, escorted from royal apartments to a small house on Tower Green, that belonged to the gentleman gaoler Sir Nathaniel Partridge….

A world away in terms of status, in one she would sit on a throne under canopy of state as a Queen. Now she was appropriately in this small house as simply Lady Jane Dudley, the wife of a commoner.

20th July

Helen Castor – Earl of Arundel leads deputation of the Council to Mary to beg pardon.

Helen Castor – The views of the people are key to this story. We could say that Mary won because she had superior forces but why did she have superior forces? Because the people didn’t believe in Jane.

Jane’s story tells us a lot about what we take to be the rules of government. Jane was proclaimed Queen by the regime in power according to the will of the dead King. The people knew that Mary was Henry VIII’s daughter, even if the law said that she was illegitimate, they believed that she, not Jane was the rightful Queen of England.

John Guy – Mary knew it was politic to be merciful. Jane is kept in confinement.

Helen Castor – Jane’s mother predictably pleaded that the Grey family had been the victims of Northumberland. Mary saw Northumberland as the sole architect of the coup.

Was Northumberland really to blame for everything that happened? Was he alone responsible for the coup or was he a convenient scapegoat for others who wanted to distance themselves from the events of July 1553?

Joanne Paul – That is the big question. It has been debated for almost 500 years. Was he is scheming Machiavellian who takes this poor innocent young girl and places her on the throne? Or was he a genuinely caring person, who cared about his country, cared about his family and was educated and talented?

Stephan Edwards – It was entirely normal for people in this period to seek personal advantage and that did so, he was simply reflecting the culture which in he lived and he was doing what everyone else around him did.

Helen Castor – We do know what Jane herself thought of Northumberland.

John Guy – On 29th August Partridge threw a dinner party and those present included the author of ‘The Chronicle of Queen Jane’, the most reliable source and Lady Jane herself. In the course of that dinner they must have been reflecting on what had happened and the general situation and Jane suddenly denounces Northumberland and says that he was the source of all her and her family’s troubles and the reason for this was Northumberland’s exceeding ambition.

Helen Castor – Jane’s trial on 13th November was the first time she had left the Tower since she had entered it as Queen in early July.

Leanda de Lisle – Jane could have been tried in Westminster Hall, taken by barge privately but instead she was processed through the streets on foot.

Treason trial – a morality play – a demonstration of Jane’s guilt. She was dressed very dramatically entirely in black and she had hanging from her belt, a prayer book. She was setting herself up as an example of Protestant piety.

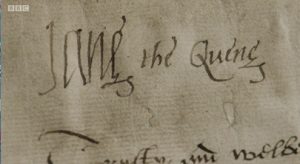

Trial opened with a Catholic liturgy which Jane must have found extremely irritating and upsetting. Listens calmly to the accusations laid against her for treason, which include signing documents as Jane the Queen and she pleads guilty to treason.

Helen Castor – But was Jane guilty? She was a teenage girl who had played no part in trying to take the throne. Was Jane an innocent victim?

Stephan Edwards – Depends on how you define innocent? In purely legal terms, probably not because she did actively participate in the events of her reign. She asserted herself and refused to make Guildford King, she willingly signed numerous documents, took the action of locking her Privy Councillors into the Tower. All of those are very positive moves on her part to assert herself as monarch. Legally no, she is not innocent.

Helen Castor – But in an extraordinary act of leniency, Mary suspended Jane’s sentence.

John Guy – Mary, particularly at this stage of her reign is generous, merciful and also very pragmatic. She knows it is wise to build up support where possible at the beginning of her reign.

Helen Castor – Mary needs to consign the crisis to history as quickly as she can.

John Guy – It is well within Mary’s character that because Jane was family, even despite all that had happened she could have brought her into her court and rehabilitated her.

Helen Castor – But unlike the Duke of Northumberland, Jane was not prepared to change her faith at any price.

Leanda de Lisle– She was prepared to die for her religious cause. Jane had one way of reaching the outside world. As a child she had been schooled in writing letters.

James Daybell – Letters are a political tool. They are powerful communications.

Helen Castor – As Queen, Jane had signed letters prepared by professional scribes. Now she put her own skills to work and gave full vent to her faith with no concern for the consequences.

Leanda de Lisle– Jane hears that Mary has relegalised the Catholic Mass. Jane violently disapproves of the Catholic Mass. She wants people to take a stand against it, so she writes an open letter to a former tutor of hers, who has converted to Catholicism and says people should rise, rise again in Christ’s war.

Helen Castor – At the very moment when Jane needs to be appealing to Mary as her life hangs in the balance, the writing of this letter is remarkable.

Stephan Edwards – It is a very forceful letter, full of extremely strong language. It violates all sort of social norms, this is a young girl speaking to an older man, this is a student speaking to her former teacher. And in each of those roles she has reversed it and become the authority.

Helen Castor – The extraordinary thing is that Mary overlooks this letter. Even now she won’t sign Jan’s death warrant.

Jane is left languishing in the Tower. The process of wiping away the pictures and records of Jane the Queen begins and after all this time looking for traces of Jane, I still don’t know what she looks like.

Stephan Edwards – We live in an era today of visual media. Unfortunately we don’t have a reliable, authenticated, documented portrait of Jane Grey.

Helen Castor – What are the options for the possible images that we might look at to try and see Jane’s face?

Stephan Edwards – There is really only one at the moment that gives us reasonably reliable indication of her appearance and that is a portrait at Syon House.

Helen Castor – If there were ever more paintings of Jane then it is possible they were destroyed as she awaited execution.

The Syon picture, long said to be Jane Grey was analysed in 2013 by experts able to date the wood it was painted on.

Stephan Edwards – It was painted 50 years after she died. But we do know that it was commissioned by someone who had actually known Jane.

Helen Castor – This painting is as good as it gets.

Helen Castor – Now Jane was out of sight, she was out of mind. Mary was focused on her own future. She had announced her intention to marry Philip of Spain. Mary was working to undo her brother’s Protestant reforms. Catholicism with all of its ritual returned.

Jane glimpsed the world through narrow windows and conversations with the few who still came to visit, including her father, Henry Grey. But while she was in prison another plot was being hatched. In January 1554, Thomas Wyatt, a Protestant gentleman raised 4000 men to march on London to remove Mary from the throne. We don’t know if Jane knew about it but she was implicated all the same. Alongside the rebel leaders was one man who for so long had worked to advance the Protestant cause, her own father.

Jane would have heard that the uprising collapsed in violence and chaos and was routed by the forces of the crown. And there could be no pardon for Jane’s father this time, Mary had forgiven him once, she couldn’t forgive him again. When Jane refused to let her father lead the army to confront Mary in Framlingham she probably saved his life and had her father lived a quiet life at court under the new regime, there’s a chance Jane could have been saved.

But now, her father’s actions were what sealed Jane’s fate. While she was alive she became a symbol, a rallying point for rebel Protestants. Mary couldn’t let her live. Mary signed the death warrant for Guildford and for Jane too. And for Jane’s father, perhaps the greatest punishment of all, he would live long enough to know his daughter had been beheaded.

Sally Dixon-Smith – The vast majority of executions associated with the Tower of London, happen outside the castle on Tower Hill in public, for justice to be seen to be done. This is what happens to Guildford Dudley.

But for Jane herself, she is one of a very privileged group of people who are actually executed, privately within the castle itself. Between 1483 and 1941 there are 22 executions that happen within the confines of the Tower and Jane is one of 5 women who are executed within the castle and one of 3 queens.

Helen Castor – There is an account of Jane’s private execution which is the most reliable account of this infamous event. It is in the ‘Chronicle of Queen Jane’, written by someone who was present inside the Tower.

Another source says that she conducted herself at her execution with the greatest fortitude and godliness.

It’s a terrifying thought, Jane had to walk out here, lay her head on the block and wait for the blade. When we talk about Tudor history, we use words like beheading without thinking too much about them but Jane’s death was a moment of horror.

She was executed on the 12th February 1554, dressed head to foot in black, carrying a prayer book in her hand, supported by 2 devoted gentlewomen.

It may be the end of Jane’s life but this is where the enduring fascination with the nine days queen begins. The story of how this young woman met her death has been repeated throughout history and in the process her execution has become shrouded in myth.

There is another famous description of her execution. It is an account published in the weeks after Jane’s death by an underground Protestant press, in other words by someone who had an interest in making Jane a perfect Protestant martyr.

It describes her last moments in heartrending detail. It is full of pathos but it is an example of how Jane’s story has been embellished because it was added in to the eye witness ‘Chronicle of Queen Jane’ when it was published in the 19th century.

John Guy – When this was edited in 1850 by John Gough Nicols, who was a very distinguished historian, he altered the text. This is very, very hard to believe but he added new text that he believed to have been written by the original chronicler that he had found elsewhere. They were texts that were circulating quite widely, even in the sixteenth century but he added them for the extraordinary reason, and this is the thing about Jane Grey that you couldn’t possibly have made up, he added it because he had recently seen Paul Delaroche’s painting.

All the pathos, all the drama of the version of the story that has Jane grey coming to the scaffold and then fumbling with the blindfold and groping for the block, asking the executioner if he will do it before she has knelt down at the block and he says no, and then saying the psalm. The wonderful theatrical, dramatized, creation of Jane as this innocent victim and Protestant martyr, this is not in the Chronicle of Jane Grey.

Helen Castor – The 19th century editor was inspired to include this description of Jane’s execution, in the otherwise eye witness chronicle by one of the most popular portraits in the National Gallery.

The execution of Lady Jane Grey was painted by the French artist, Paul Delaroche more than 250 years after Jane died.

Stephen Bann – What is not is a historical reconstruction of the actual circumstance in as far as we can know them, of Jane Grey’s execution.

Helen Castor – The painting was first shown in 1834, 30 years after the end of the French revolution.

Stephen Bann – Inevitably it brings up events in French history which were too raw to be depicted at the time.

Helen Castor – What Delaroche was not striving for was historical accuracy about 16th century England.

Stephan Edwards – It is such a rubbish image, the only thing accurate in that image really is the straw on the floor. Beyond that it is almost entirely histrionic, dramatic evocation of an idea rather than the depiction of an individual.

Helen Castor – Do you think the difficulty of seeing Jane’s face is one of the things that has left space for the crowding in of myth about her, that it is harder to have a sense of her as a real person.

Stephan Edwards – It makes it very difficult to render her concrete. There is a mystery and a vagueness about it which leaves room for infill.

Helen Castor – At times those gaps in the record have left room for complete invention. One of the best examples appears in the Nine days Queen, written by Richard Davey and published in 1909. His source is a letter from a Geonese merchant, Baptista Spinola. This letter describes Jane in great detail.

Here are the pitfalls of history, this, after her execution, the most often repeated detail in the story of Jane Grey, turns out to be a historical fraud. And that rich merchant, Baptista Spinola, most probably never existed.

Leanda de Lisle – It fulfills people’s expectations, they want a pretty girl, who looks vulnerable and fragile, surrounded by big adults.

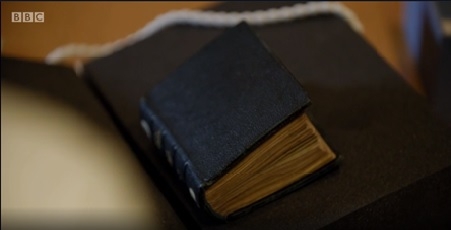

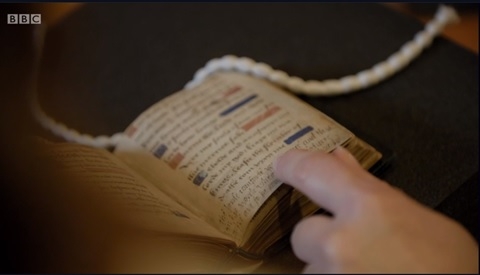

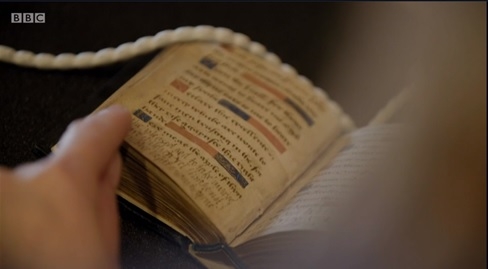

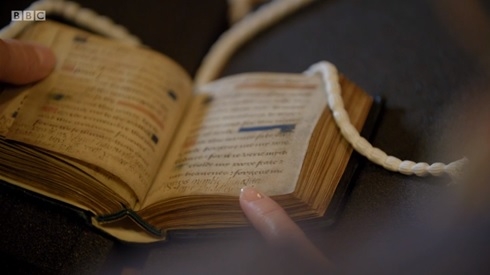

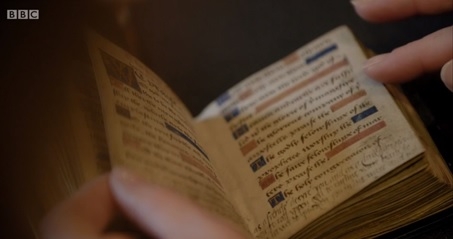

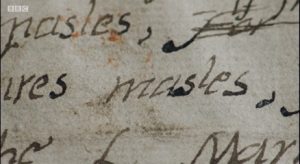

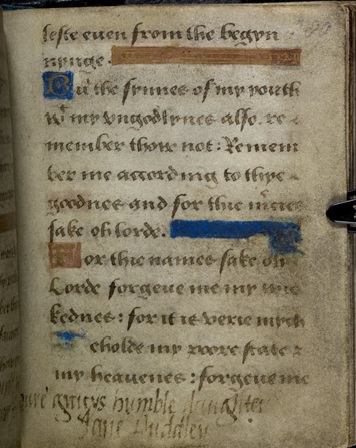

Helen Castor – From the moment she died, people have mythologised and misrepresented Lady Jane Grey. But there is one object that allows us to hear Jane’s own voice from beyond the grave, her prayer book.

Helen Castor – So this is the book she actually carried onto the scaffold and handed over just before the blindfolding and the kneeling.

Andrea Clarke – It is quite incredible, isn’t it. What makes it even more special, one of the great treasures of the British library, Jane wrote some messages in it.

Helen Castor – One is a heartfelt message to her father.

Andrea Clarke – She writes, ‘The Lord comfort your Grace and that in the word we’re in, all creatures can only be comforted.’

Helen Castor – ‘And though it hath pleased God to take away two of your children, yet think not that you have lost them but trust that we, by leaving this mortal life, have won an immortal life.’

Andrea Clarke – And then she signs it, ‘your grace’s humble daughter, Jane Dudley.’

Helen Castor – She is no longer Jane the Queen.

In another message, she writes to the Catholic gentleman who had been in charge of the Tower during her time in prison.

Andrea Clarke – ‘I shall as a friend desire you and as a Christian require you, to call upon God to incline your heart to his laws and to not take the word of truth utterly out of your mouth but live to die.’

She is saying, don’t be misguided by false teachings and by that she means Roman Catholicism.

Helen Castor– Once we strip away the layers of myth and exaggeration, the Jane we find is devout, unflinching, composed to the end.

But the one thing she could never be, is the one thing that might have made a difference to her chances of keeping the throne. Her cousin Edward’s plan for the succession makes it clear that he thought that a man should wear the crown.

To hold power meant to be male.

Leanda de Lisle – Women were considered to be creatures of emotion, rather than of reason.

Helen Castor – Edward’s plan had to be to keep women off the throne for good.

Stephan Edwards – No one has yet looked at it as a gender issue, as opposed to a political power or religious issue.

Helen Castor – But as it turned out Jane’s nine day reign was part of a critical moment in English history. She was overthrown by her female rival, Mary who would rule England for 5 years.

Helen Castor – When Mary died, Elizabeth followed her onto the English throne. Another woman, another queen. Like Jane, she was a religious reformer, unlike Jane, she ruled for 45 years.

And Elizabeth learned a lot from Jane’s brief reign.

Leanda de Lisle – It is very important the impact it has on Elizabeth. Why is she the ‘Virgin Queen’? Well, she saw what happened to Jane when Jane married Guildford Dudley, how that helped undermine her position. She has seen how little she can trust the protestant nobility, who were supposed to be her chief backers. Elizabeth has seen how they can’t be trusted and how the ordinary people might help to save her.

Helen Castor – So Jane’s nine days do leave a legacy. But was she Lady Jane Grey or Queen Jane?

Stephan Edwards – She reigned for nine days. She was a Queen of England. A contested Queen but a Queen nonetheless.

Helen Castor – 1553 was an extraordinary moment in English history. For the first time ever, all possible heirs to the crown were female. The men who surrounded the throne imagined that the only way a mere woman could rule was as their puppet. That was why they chose Jane Grey but in her nine days as Queen, Jane began to show them they were wrong.

It was a lesson hammered home by her cousin and rival, Mary and the example of these two women in the summer of 1553, demonstrated that a Queen could rule without a man to control her, if she had the support of England’s people.

We call her Lady Jane Grey not Queen Jane because we know how her story ended but in reliving the drama of her nine day reign, we are reminded just how close she came to ruling England and how different things could have been.